Crisis generates a primal response in most human beings – fight, flight or freeze. This primal response is shaped by forces beyond our consciousness and seems to come from the core of our beings.

In heated conversations at the dinner table, on the news, in the streets, and in quiet and public protests, we see cultural codes at play that shine a light on national identity as much as sub-group affiliations. In other words, what it means to be American or French, or what it means to be a climate activist, a single parent, or a student.

That ubiquitous symbol of the pandemic, the face mask, is an icon of these tensions. Decoding this symbol of the 21st century reveals cultural tensions we struggle with as individuals, groups and nations. It reveals our trust or distrust in the societal power structures, information architecture, and how we view safety, civic duty, or personal liberty.

Triggers for cultural tension abound and we are perpetually in high-alert mode, scrutinising conversations, policy, and government actions, family, community, and yes, corporations and brands.

Pivoting communication

In crisis our cultural antennae are up. Communication needs to tune into the right frequency to be heard. And once tuned in, it needs to resonate at a new level.

What may have served brands well before the crisis may need to change now.

KFC edited their slogan to be culturally sensitive. From ‘It’s finger licking good’ to ‘It’s good’. Similarly, Coors pulled their ‘Official beer of working remotely’ ad to avoid being perceived as insensitive to the times.

Most of the time, brands play defensively against cultural codes; ‘Don’t break any rules or ruffle any feathers’. But what if you wanted to adopt a more proactive, culturally resonant strategy? And nourish your brand with positive meaning and build for the future? Well then, it’s time to invest in building cultural equity.

Understanding cultural impact

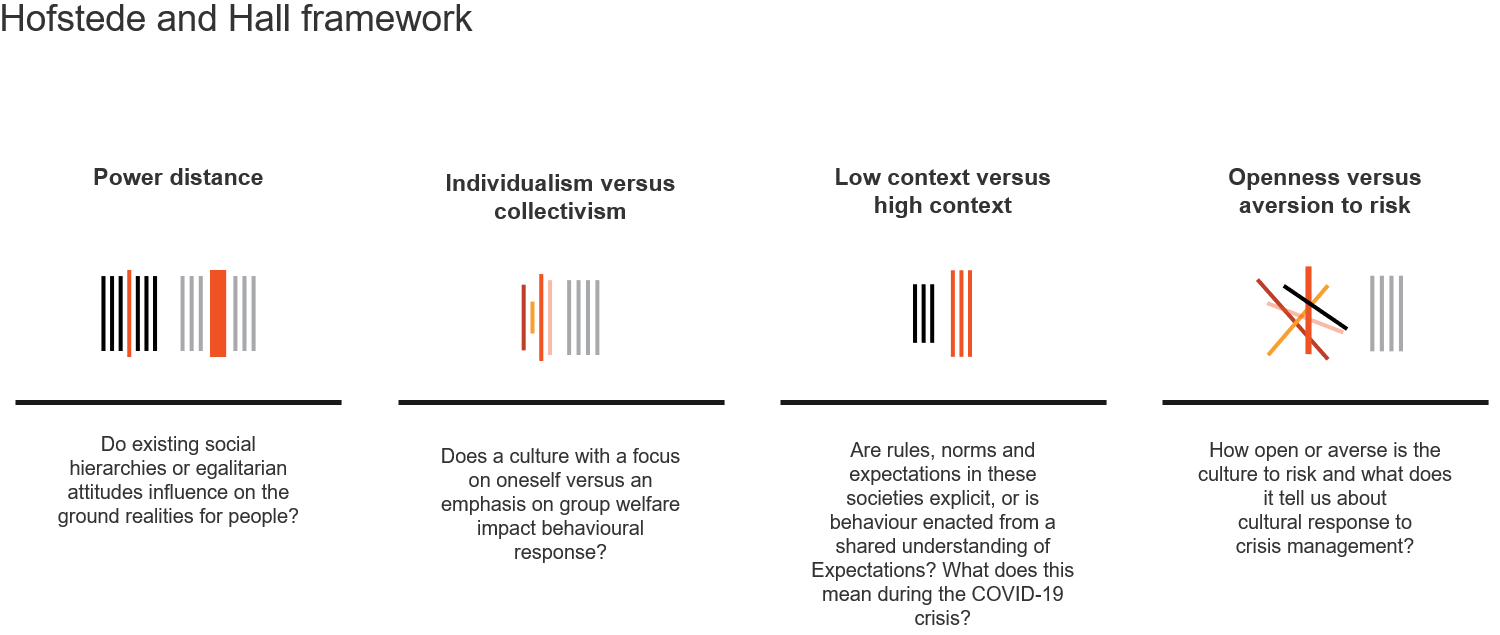

We conducted a 12-country qualitative research study to explore how people are living, feeling and acting in the context of COVID-19. We used the value dimensions framework of Geert Hofstede and Edward Hall (see below) to pin down the cultural frequencies and tonality of people around the world. It was not enough to know that people in India or Mexico were more anxious about complying with social distancing rules versus Australia or the Netherlands. It was important to understand what in these cultures made it so, and what that meant for designing persuasive communication.

Understanding COVID-19 behaviours and future tensions

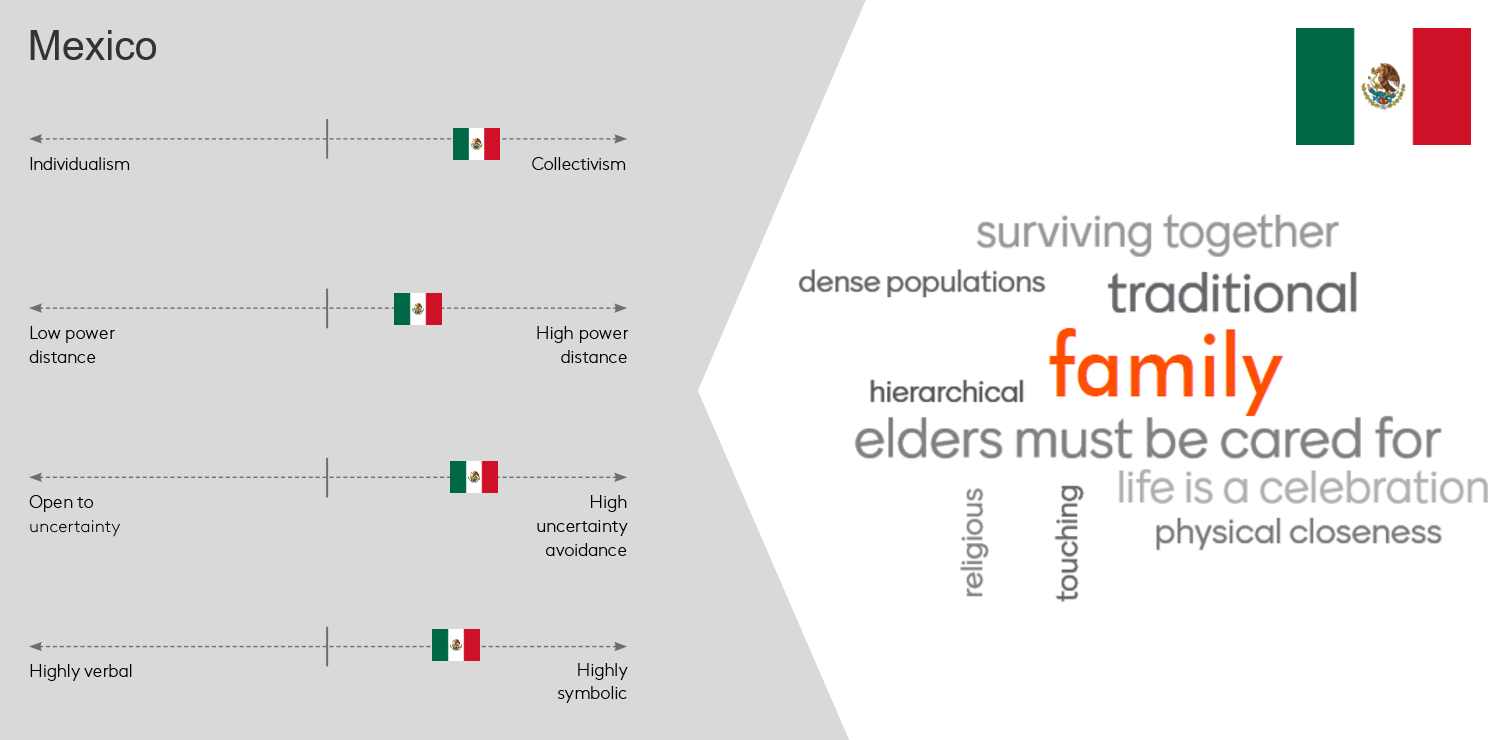

These dimensions are not a singular lens to explain a country’s cultural values. The four dimensions interact with each other and shape a unique cultural profile. Two countries that are collectivist (say, India and Mexico) may have more in common with each other than with a country that is individualist (the UK or Australia), but there are still values that are unique to each. When studying the cultural makeup of each of the countries in the research, we explored each dimension in isolation and in combination, and developed a cultural thumbprint for each that looked like this.

Understanding cultural codes

Collectivist cultures

Highly collectivist cultures tend to value social cohesion above all else, and their behaviours are directed at preserving the group rather than individual interests. The community is the safety net in a crisis, and communication that is framed to the community’s reality rather than an individualised context has a better chance of being persuasive. Messages about individual risk fall flat because they ignore structural realities of gender, race, and religion in the group experience.

Mexico is a collectivist, relationship-oriented culture where the notion of a traditional family is held dear, and physical and emotional closeness is vital to wellbeing. Densely populated cities and towns normalise physical proximity among strangers, free-spirited and family-style celebrations, and tactile displays of affection. Rural communities depend on their neighbours for survival. Failure to care for the elderly, particularly within one's own family, is stigmatised.

Little wonder then, that social distancing and face masks are a challenge to fit into their reality. The pandemic and the resulting changes in lifestyle have created new cultural tensions. Young Mexicans have set ways to honour time with elders and family. Curtailing time outside the home has meant that the clear boundaries between their own cohort and the elders has blurred. Unlike in an individualist culture where private space is respected, in collectivist cultures, there has to be a careful renegotiation.

Pringles’ MVP campaign successfully tackles this cultural tension. Pringles in Mexico walks the cultural tightrope. They serve a tightly-knit, young community – gamers – in a highly collectivist macro society. The pandemic has accentuated the cultural tension between these two worlds (young gamers must disconnect from people in their real worlds to connect with their online community). Pringles launched a Gamers Day initiative called MVP (Mum Valuable Player). A time-limited, inclusive initiative to help Mums of gamers enter their kids’ online world and experience it; a moment of connection, a bridge between two worlds. It was meant to create empathy among the elders for the world of gaming, and thereby for their kids’ personal space.

Individualist cultures

Contrast this with the UK, a highly individualist culture, comfortable in their bubbles and respectful of boundaries and personal space. Personal liberty is a cherished value and results in a high trust in the individual to do right by themselves. This explains the resistance to any imposed rules that seem to challenge autonomy (travel, communing). The UK is very clearly moving towards a recession – unemployment and inflation place household budgets under massive pressure. But the British do not do sentimentalism; it’s awkward.

Downplaying vulnerability (physical and emotional) is a British value and brands struggle to get their tone right – to show they care without seeming over the top. Sentiment is acceptable when it is directed at others (e.g., caring for the NHS) but when talking about oneself or people like us, the British way to acknowledge vulnerability is either by ‘getting on with it’ or ‘making light of it’. Resilience and self-effacing humour are acceptable ways to show empathy in times of crisis. It is worth emphasising that humour that is directed at others is a big no-no, especially in these times.

IKEA exemplifies a brand speaking to the zeitgeist without referencing the pandemic directly. It creatively addresses the lockdown impact on sleep, without demonising it, and shows how their mattress range can help.

The Aussie way of life

Having explored the impact of collectivism and individualism, let’s look at the impact of ‘power distance’ from the framework on cultural response. The UK and Australia are both highly individualist, but Australia is unique because of its low power distance (the intrinsic flatness of the Aussie way of life versus the stratified British society). ‘Mateship’ is a cherished value in Australia and translates to everyone having a fair go at life. Personal space is valued, and the family setup is typically nuclear. However, the current pandemic hit Australia straight after their worst bushfire season, so the value of communities banding together is very resonant.

Oneness with the physical environment, which was always important, took on a new meaning. The sense of Aussie pride and optimism, the need to recalibrate emotionally and to keep seeing the upside has rarely been stronger. What would it look like for a brand to offer a respite from the grim every day?

See the contrast between the Dominos ads in the US and Australia, both communicating the same service, to see what’s uniquely Aussie. Both ads talk to the mindset that fears the world outside and provide the reassurance to get on with life (that is, get a takeaway). The Aussie ad taps into surrealistic humour to elevate a service designed to allay fear and resume life in a time of crisis, whereas the US ad is funny but quite literal.

The importance of culture

Culture has always been important, but it has operated in the background; brands acknowledged the impact of culture usually when a cultural code was broken. Culture is firmly in the foreground today as the pandemic affects communities and elicits a visceral response from us.

Cultural understanding offers brands an opportunity to spot growth potential in a crisis and create a point of difference.

The fortunes of the Walt Disney Company, M&Ms, and Revlon were shaped by great crises of the last century: Crash, Depression, World War. Culture was being reshaped and these great brands reshaped their services to create value in these epic moments.

In a polarised environment with increasing parochial rhetoric and diminishing physical, emotional and financial safety, forward-thinking brands will stay ahead by rethinking their cultural relevance and investing in building cultural equity for their innovations, communications and activations.

Please get in touch to learn more about the study and how to find the right cultural codes to build long-term brand equity.